Hand this to readers of The Fisherman and The Rust Maidens who like their folk horror slow-simmered with a regional spine. Strong sense of place, tactile rituals, and a moral quandary that will spark book-club debate. Content notes: influenza loss and war trauma, body horror focused on eyes and food storage, animal harm in brief, religious fervor, economic precarity. Best for adults or mature older teens who are fine with lingering dread over jump scares.

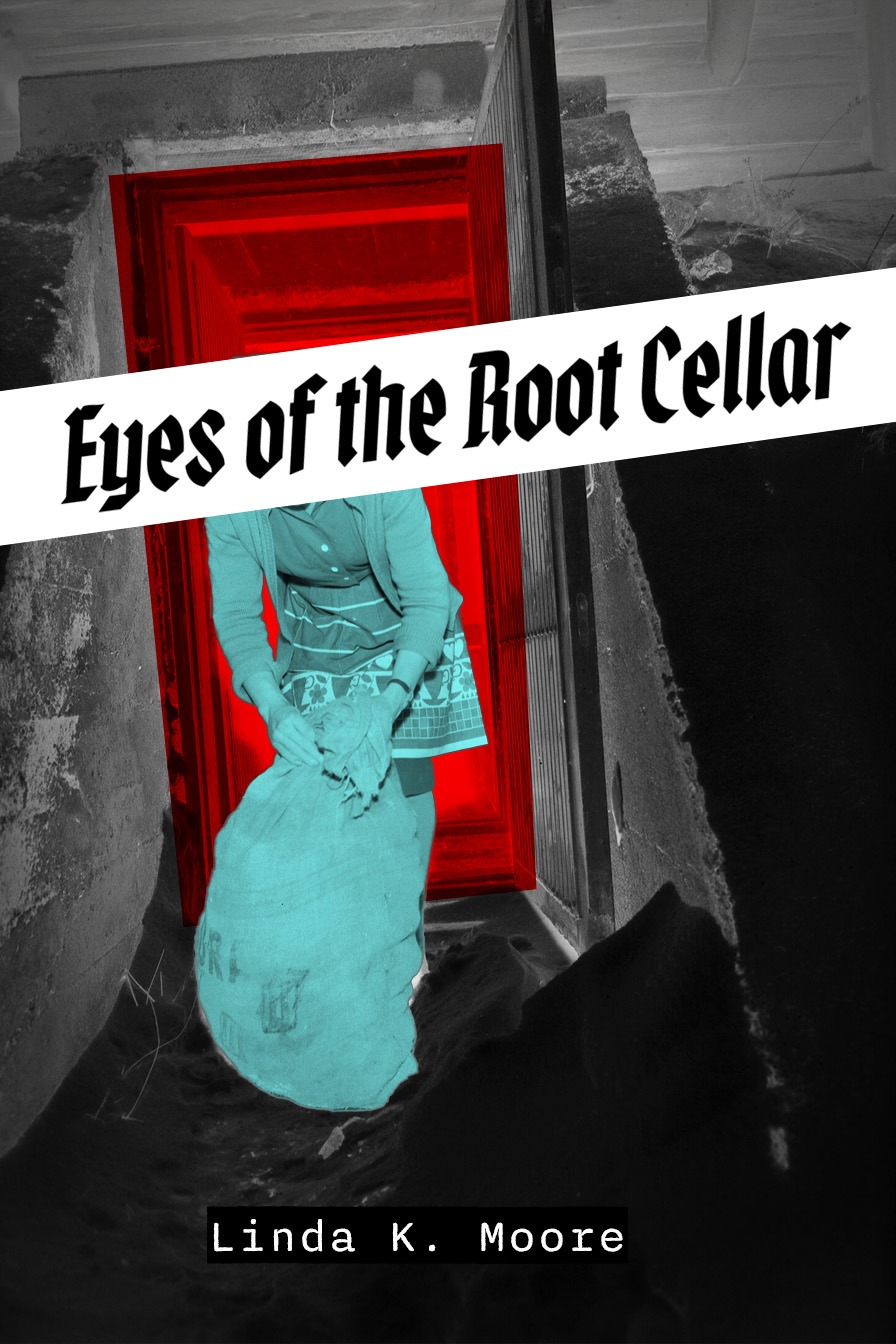

What if a pantry meant to keep winter at bay instead kept something else alive? This unblinking tale of buried hunger and folk justice unearths a dread older than fences, colder than creek water, and patient as stone, set among the hills and hollers where salt-cured secrets outlast the people who try to forget them.

Pine Lick, West Virginia, 1919. Fresh from the influenza graves and a ragged war, Cora Ellison returns to the weather-beaten farm she fled as a girl, her mother newly dead and the bank at her door. The only thing that still feels faithful is the root cellar: a low, limestone throat beneath the kitchen, cold and damp, its shelves stacked with wax-sealed jars labeled in a careful hand—Peaches 1897, Tomatoes 1903, Dandelion Wine 1911—each jar set by the woman who taught Cora the art of keeping. But the cellar has inherited more than canning instructions. When lamplight lowers and the iron hasp clicks shut, Cora feels the press of a gaze. Not the gaze of mice or men—the other kind.

Old Tamsin Grigg, a midwife with a pocket full of red thread and rusted keys, warns Cora about the house under the house. The stones were laid by Ezekiel Keating, a famine immigrant who carted them from a burial mound upriver and whispered to the earth until it listened. He called the mouth below Seed-Mouth, and fed it the peelings of saints and sinners alike. "You give the ground your looking, and it gives you back what you can't stand to see," Tamsin says. Cora laughs until, in the glassy curve of a Mason jar, an eye opens where a peach pit should be—and blinks.

Sheriff Rhys Danner chalks up the bruited visions to nerves and grief. Reverend Pike preaches the gospel of cast-iron repentance. Dr. August Bell prescribes bromide and long walks. But across Cold Spring Township, potatoes sprout lashes, knot-holes in barn boards bead with wet, and children dare each other to crawl into the culvert that runs from the old Silver Crook Mine to the Ellison springhouse, where the water tastes faintly of penny and rain. A farmhand vanishes. The Gazette prints the shape of his hat brim in mud, then runs out of ink to explain it.

At night the cellar whispers the names of the dead and the not-yet-dead, Cora's among them. It promises to fill the pantry, to keep the sheriff from pinning pink slips to her posts, to set a warm plate before her shell-shocked brother Joshua if she will pay the tithe all Ellisons paid and pretended they did not: the third jar of every season, and one eye to watch with. When Cora, in a moment of fear and faith, drops a rooster's eye behind the old stacked stone, the garden explodes in green and the debt collector shakes her hand.

Soon neighbors stop saying "no such thing" and start bringing jars. Meat turns sweet. Roots grow like ropes. The cellar watches through them all. Joshua begs Cora to burn the door; Tamsin says to leave the lid on the world. The Harvest Social comes, fiddled bright, and as the tables groan with bounty, the jars in the church basement pop their seals like knuckles. Glass sings. Brine runs. The floor is bright with rolling sight. People stumble to their knees, hands to faces, while the cellar door up the hill swells as if it were breathing.

With Pine Lick poised between the grist of a mill and the maw of a well, Cora must decide whether to blind the land to save the living or open the stones and let the old hunger see daylight. The price of mercy has a weight; the price of truth has a taste. Only one thing is certain: under the clay, under the shelves, under the names we give our keeping, something that remembers being starved is watching—and it does not blink first.