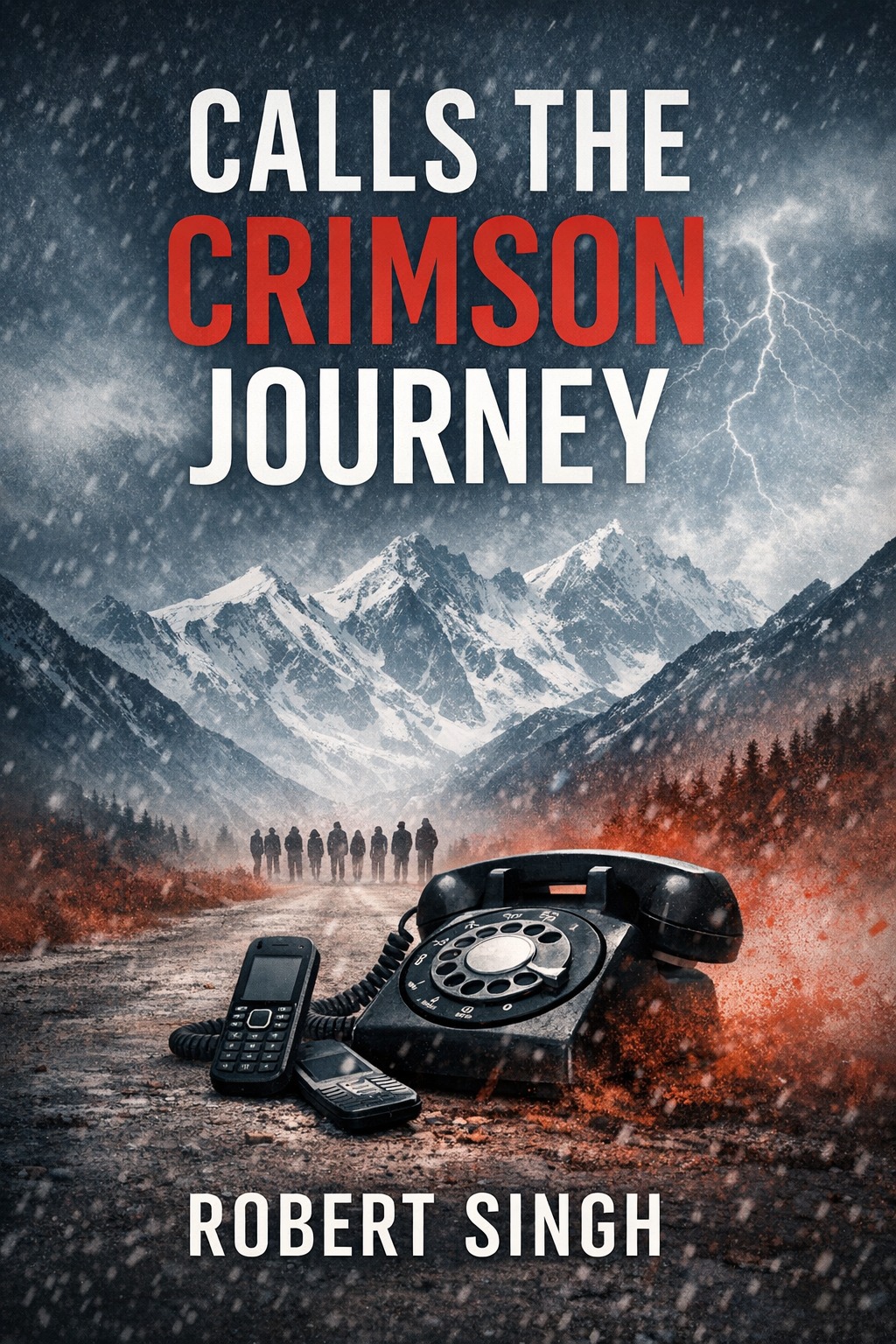

In the first days of October, with a storm plating the Homathko Icefield in blown glass and fine red dust from late-summer fires, nine travelers meet on a decommissioned forestry road beyond Tatlayoko Lake. Each has received the same impossible call on a jumble of machines—burner phones, a rotary in an Anahim café, a satellite handset forgotten in a SAR cache: a child's voice reciting a few halting lines from a Chilcotin cradle song about ravens carrying maps in their bellies, followed by a coordinate stamped into silence. In the subject line, for those who even had email, the words were always the same: Calls the Crimson Journey.

The benefactor who foots the floatplane and caches drums of white gas along the Klinaklini is a name only—Havel Isbister—an eccentric philanthropist with a small office above a marine chandlery in Bella Coola, well known to conservation boards and quietly hostile to cameras. The goal sounds simple enough: ferry a brass transit compass that belonged to the dead guide Eamon Jack to the cairn on a nunatak they all climbed with him years ago, and by doing so, make good an old promise. Their party is a slantwise roll call of the coast and plateau: Mira Dhatt, a cartographer who reads the world like paper; Lio Serrano, glacier guide and bolt-repairer; Maeve Keating, retired lighthouse keeper from Boat Bluff; Dr. Jun Nagata, entomologist with a jar for every wing; Tom Spence, ex-logger with a scar like a contour line; Priya Sandhu, museum curator with accession numbers for every absence; Callum Reid, SAR coordinator; Penelope Baird, an environmental lawyer whose filings are neat as switchbacks; and Noah Chen, a teenage archivist whose orange toque makes him visible even in fog.

They follow a red pencil trace copied from a 1923 National Topographic Series sheet, an old line Mira finds is not a route so much as a helix thrown over crevassed basins, intersecting known avalanche paths; someone is shepherding them through risk. At the first cache—the metal lid of a biscuit tin wired to a krummholz spruce—they find a cedar plank with syllables burned into it, a fragment of a surveyor's ballad, and a rusted piton stamped with an accession number that Priya recognizes from a scandal hushed at the city museum. Red iron oxide powders their gloves. A flare kit in the drum misfires and paints a snowfield with a smear that looks too much like blood. A snow bridge drops under Tom's weight and leaves him with a breath like torn paper. A swarm of alpine yellowjackets erupts from a rotten windfall that has been salted with sugar. On the flank of a moraine, a bear's paw print has been dressed with red ochre and a knot of kelp fishing line laid beside it in a coastal hitch that only a handful of loggers still tie.

At each hut, shack, or eyrie they sleep in—the tin-roofed trapper shelter on Scar Creek, the skeletoned fire lookout above Anahim Peak, a bivy under the Himmelhorn's western tooth—another object waits that spools backward into one of their lives: a charred thermos branded with a ferry emblem Penelope once tangled up in litigation; a Polaroid of a schoolyard where Callum made the call to stand down a search too early; a lighthouse oil can that knows Maeve's midnight shortcut; a broken cam with filings that match Lio's kit; a brass tag that should have hung from a mask in a coastal collection Priya miscatalogued. The child's voice calls again each dusk, counting down turnings in a lilting cadence. Accidents begin to rhyme, or else folklore becomes a set of instructions no one remembers agreeing to.

When the pilot contracted to retrieve them is found in a moss-choked seep below a blue-ice wall, radio throat sliced with old fishing line and a flashlight placed like an altar, suspicion slides like a slab across the group. It is easier, Mira realizes, to map blame than to map weather, and harder to distinguish the two when the isobars tighten. Jun, who knows the patience of insects and the pattern in their sleeping swarms, and Noah, who can read a ledger as if it were a river, help Mira notice the tell: the voice is spliced, a mosaic of wax cylinder recordings held in the museum's basement and digitized in a rush, the hiss of shellac under every word. The trigger is not a time but a place—geofenced into their GPS units by a line of code written by someone who once taught himself mapmaking on cheap software. Every cairn blooms with red because someone wants to know who touched what, and when.

At Waddington's Nunatak col, Callum vanishes on a short approach, his rope cleanly cut with a rim of glass from a broken glacier bottle. Tom, pale and cracking as if the cold can reach his marrow, denies the worst accusations and coughs the name the rest refuse to say aloud: Eamon. The dead guide who wasn't. The man they are carrying a story for because the truth weighs too much; the one person who knows each of their private ridgelines where a false step years ago left somebody else in a crevasse.

The last coordinate leads them to a seep-fed tarn known in old stories as K'ala Gwaay's Eye—crow water—halfway to the Kingcome divide, where wind combs the sedges and a parabolic microphone waits like a glass ear. Eamon Jack is alive, wrapped in a SAR parka turned inside out so the reflective tape disappears, watching them on a ridge with a field notebook banded in bicycle tube. He has not built a murder machine so much as a courtroom without a roof. He wants names, not bodies. He wants the kind of confession he has never been able to make for himself, an erasure he has spent six winters mapping into the bones of the range. What he calls the Crimson Journey is a folk-ritual pulled through a cartographic grid: a remembering no court would sanction. With the storm closing and the satphone dead, the company has to choose a line—descend into the wet green where law can find them, or climb into the wind and make a treaty with a man who carries guilt like a topographic pack.

The mystery bends from a closed-circle puzzle into moral cartography. Mira takes a pencil and draws a new map on the blank back of the 1923 sheet, not of cairns and cols but of choices, crossing lines in colors that do not exist on official charts. The final chase tacks along corniced ridgelines and drops through cedar lowland near Bella Coola, under a bear's silhouette that might only be a cloud scudding. The reveal is not a trumpet blast but a contour, and the last call—the child's voice returning from a battered kettle's whistle as tea boils on the lookout's rusted stove—does not ask who did it, but who will carry it down. There are names. There is a reckoning that does not look like triumph. The red line that brought them here does what any red line does in the end: resolves into a story about what you will cross, and what you will not.