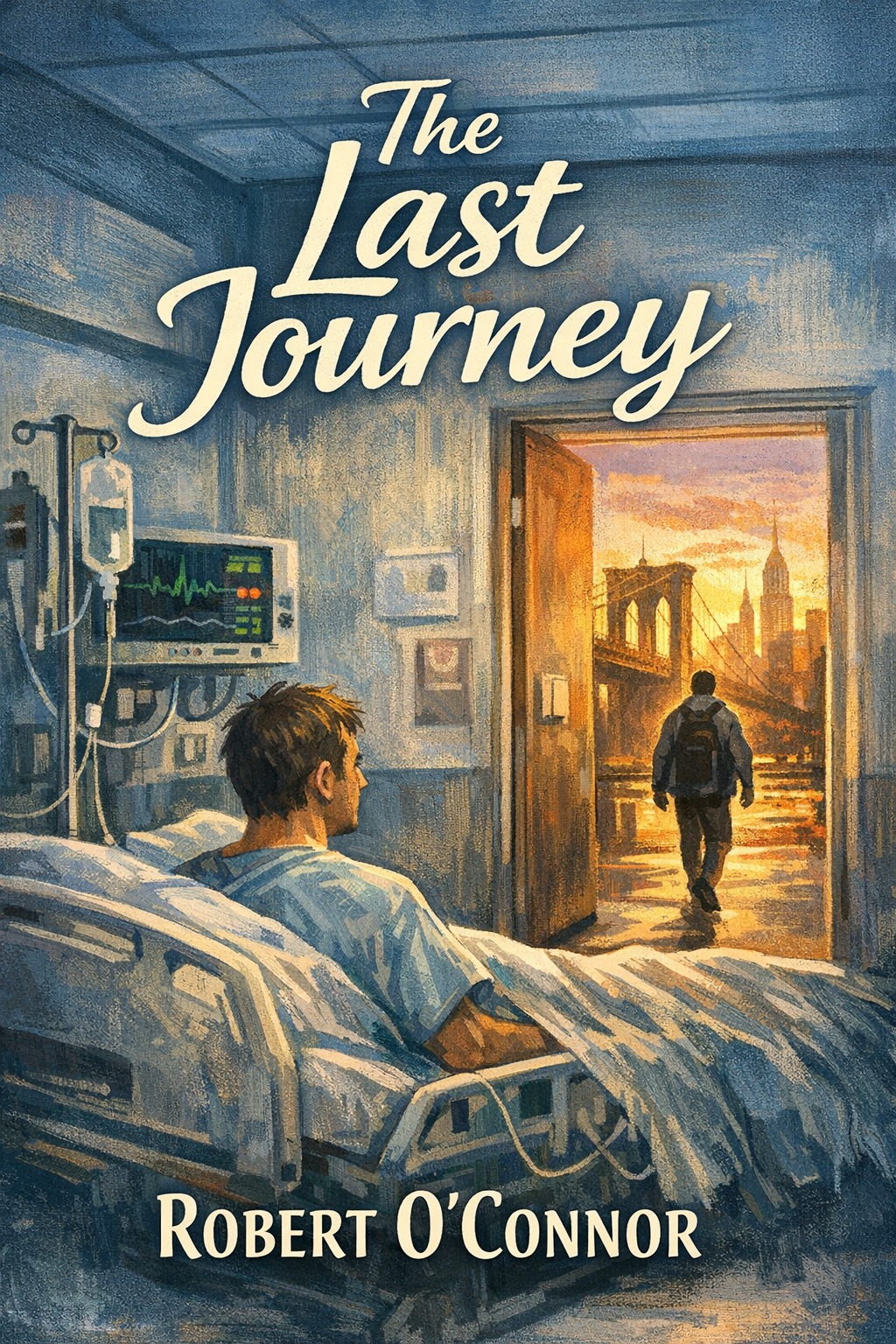

"My name is Robert, though on screens and bylines I answered to Rob O'C., O'C, and once—briefly, disastrously—to the moniker Rover. The people who love me call me Rob. And I am not supposed to be here." That is how this book begins, in a hospital room at Methodist Hospital in Brooklyn, staring at the red pulse of a monitor and a chipped enamel mug that somehow followed me from a port in Valencia to a motel in Truth or Consequences. The doctors used words like an avalanche: hypoxia, arrhythmia, polysubstance, miracle. I heard only the rattle of the air conditioner and my sister Maeve asking me if I had finally had enough.

Before the medevacs and the quiet talks with sponsors and my producers, there was a kid with a secondhand Nikon F3, ping-ponging between Connemara and Camden, New Jersey, learning the weight of a camera and the weight of silence. There was twelve-year-old Robert, who cataloged bus routes in a battered composition notebook and could recite Amtrak timetables like scripture; nineteen-year-old Robert, who skipped finals at Rutgers to chase a monsoon photograph in Kolkata and came back with a parasite and his first byline; twenty-eight-year-old Robert, who pitched a show called Borderless Tables to a streamer named Lighthouse TV and somehow found himself in a kebab shop in Gaziantep on a Tuesday night explaining to a very patient sound engineer why humble food always tastes like a confession.

If this sounds heroic, it isn't. The work was often just plane seats that didn't recline, and sand trapped in the hinge of a lens hood. It was a producer named Lila Santos who could talk thirteen languages of bureaucracy. It was an editor, Kenji Watanabe, who saved my worst ideas in the cutting room and gently strangled my best ones into coherence. It was my climbing partner, Amara Ndiaye, who hauled me across a slush bridge in the Cordillera Blanca when my left knee clicked and my right hand went numb and, later, left me alone long enough on a ledge that I had to admit I wanted to go home more than I wanted a perfect shot.

The truth I hid was not glamorous. A torn shoulder in Patagonia brought pills into my kit the way an extra battery slips between socks. The flashes of applause in Marrakesh and Bogotá only widened the emptiness. I pretended I could out-walk it—Aleppo, Valparaíso, Ulaanbaatar, Isla Navarino—until a relapse, a fentanyl-laced counterfeit rolled up like a secret, stopped my heart in a motel room with a humming ice machine and a Gideon Bible in the drawer.

The Last Journey is about the trips I sold—markets at dawn, snowfields at dusk—and the journey I refused, the one that required a passport I did not yet have. It is about the fracture lines of a family that loved me in all the wrong right ways: a mother who kept a teapot whistling in Galway while I ghosted her calls from Lima, a father who taught me knots on the docks in Hoboken and told me that every knot is really a plan for letting go. It is also about sobriety, which was not a mountaintop but a cul-de-sac in Santa Fe, at a place called Juniper Ridge Recovery where I learned to sit in a chair without an exit strategy. I talk about the show and the meals that saved me, about the people whose names never made the credits, about a dog named Ferry that taught me routines. I write frankly about why I left the camera bag in the hallway for weeks, and why I picked it up again—lighter, somehow—when the world would let me.

Unflinchingly honest and, I hope, unexpectedly funny, The Last Journey is a map folded wrong-side-out. If you are lost, there is room on this page beside me. I am still learning how to read it, too.