In this unflinching, authoritative portrait of Nero Claudius Caesar and the corrosive household that shaped him, historian Patricia O'Sullivan turns palace corridors into case studies and triumphal arches into diagnostic charts. Drawing on wax tablets from the Palatine, charred correspondence from Herculaneum, and the petty tallies of court stewards who counted everything from lamp oil to lyre strings, she reconstructs a family web as gaudy as the Domus Aurea and as strangling as its gilded vines. From the first, Rome's health, economy, and social fabric shudder beneath decisions that sprang not only from imperial whim but from habits etched in childhood: the calculus of survival, the currency of affection, the spectacle expected of a boy pushed toward divinity before he had learned restraint.

O'Sullivan follows Nero from the marbled thresholds of Antium to the sulfurous shores of Baiae, where Agrippina the Younger rehearsed embrace and threat with equal poise. She explains how this son of the Julio-Claudian house was adopted into an image as much as a lineage, molded by the careful staging of Claudius's domus and the careful erasures of Britannicus's claim. The author paints rooms in detail: ivory-inlaid beds in the Domus Tiberiana, bronze mirrors fogged at winter banquets, anterooms where freedmen Fingered signet rings and waited for nods. She traces the early years with Seneca and Burrus as a fragile tutorial in statecraft, begun under frescoes of laurel and thunderbolt, and shows how that arrangement gave way to the public theater Nero craved and the private tribunal he feared. A child promised the world learned instead the cost of every glance at the Palatine threshold.

Sifting court rumor against receipts and graffiti, O'Sullivan renders scenes that sting with specificity. A winter Saturnalia where a cask of Falernian was sent back because it smelled of pine tar; a Lupercalia processional where a dove escaped the priest's hands and the omen, recounted in a scribe's cramped hand, rippled through the barracks on the Caelian. She recounts in unsparing detail everything from the emperor's fascination with voice coaches on the Via Sacra and Poppaea's box of amber hairpins passed from patron to patron, to the appalling way he dismissed Burrus when illness made the Praetorian prefect's voice a rasp and derided the aging Seneca as a stoic actor past his role. Fires, whether domestic or citywide, burn through these pages: the night the Subura turned copper under a wind of sparks; the morning the first plaster for the Golden House was mixed with powdered marble and ambition; the quiet afternoon when Octavia's fate was sealed with a courier's seal at Ostia. By the time Rome's aurum coronarium was demanded for new spectacles and singers rehearsed under the oculus of a rotating dining room, the pattern was complete: praise as a ration, loyalty as a wager, mercy as a rumor.

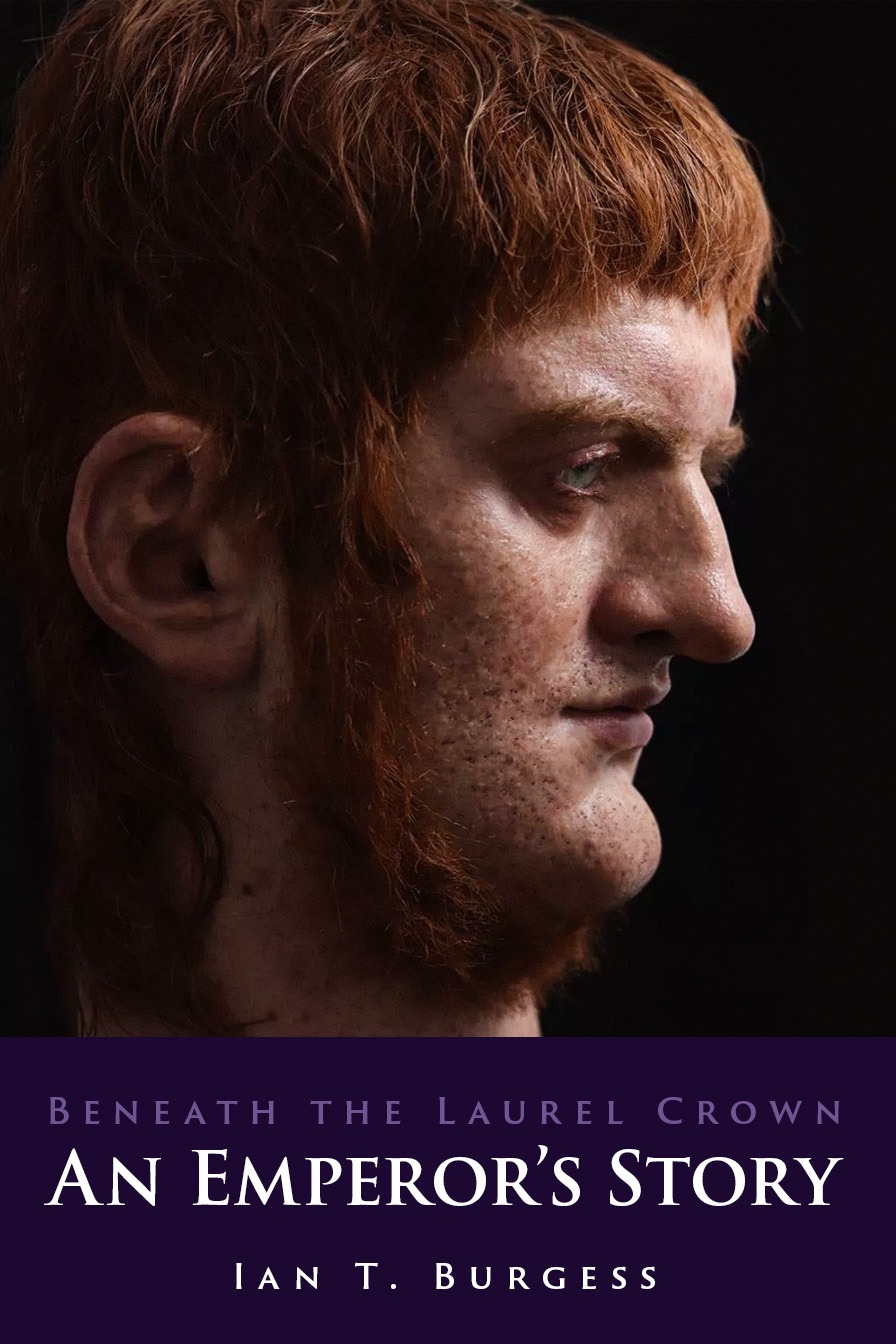

Numerous classicists and popularizers have tried to explain Nero's appetites, alternately making him monster or misunderstood artist. O'Sullivan brings the discipline of a Latinist, the skepticism of an archivist, and the human clarity of a clinician to bear on a life crowded with marble busts and missing faces. She reads coin dies and graffiti the way others read diaries, and sets the emperor's staged triumphs against the household catastrophes that authored them. From the Praetorian camp's pay ledgers to a charred shopping list from the Esquiline naming figs, myrrh, and theatrical grease, she reveals what lies beneath the laurel crown: a boy trained to perform love, a ruler schooled to spend trust, and an old dynasty that taught its last son to mistake applause for safety. The result is a vivid, unnerving saga of power learned at a family table and tested on an empire.