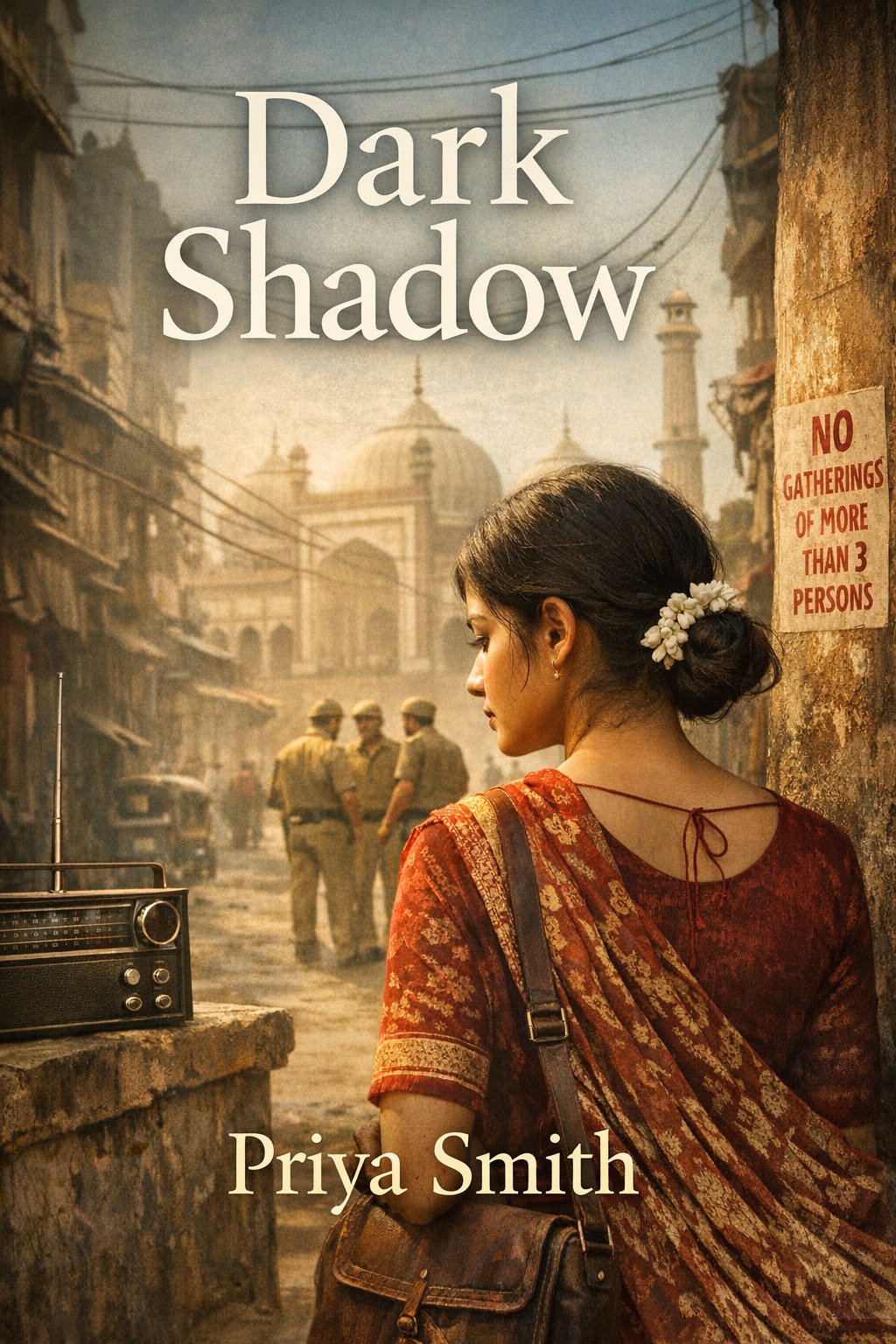

In the smothered summer of 1976, when radios hiss the same sanctioned songs and posters tell people not to gather in groups of more than three, Old Delhi learns to lower its voice. Leela Banerjee, twenty-three and fresh from Allahabad University with a degree no one at home knows quite what to do with, returns to her family's cramped haveli off Chawri Bazaar. Her mother counts sari borders and prospective grooms, while Leela counts the days since Sushila, the ayah who once tucked neem leaves in Leela's braids, vanished during a midnight sweep near Turkman Gate. Everyone insists Sushila left of her own accord. The only trace Leela finds is a fountain pen with crusted indigo ink and a torn ration card that does not belong to her household.

Asha Begum, a meticulous typesetter at the shuttered Shama-e-Hind Press in Ballimaran, has spent a lifetime aligning letters that other people will read aloud. After her husband is detained under MISA and her own son is lost to an illness the neighborhood women diagnose with crushed basil and prayer, Asha takes in her late sister's boy and the widowed neighbor's errands. She walks a little Hindu girl, Meghna, down lanes braided with power cuts and spice dust, telling stories that solder grief into something usable. When bulldozers arrive on a brittle morning and a steel-toothed official waves papers that look like nothing Asha can read, she salvages an iron composing stick and a tin box of types—the only tools she trusts to hold a line against erasure.

Parveen Singh, called Paro since she learned to boss around cousins twice her size, is a midwife whose tongue curdles milk and whose hands can coax a breech baby into the world. Short, unsentimental, and perpetually on the verge of losing work, she leaves Karol Bagh after another employer tires of her backtalk and finds a position in Civil Lines with Lorna D'Souza, an Anglo-Indian widow who keeps one teacup chipped on purpose and a ledger that lists men by badge number instead of name. Lorna's drawing room holds a reel-to-reel recorder, a clacking relic from her radio days, and albums that never made it to All India Radio once the censors began to lean. Paro suspects the widow is not collecting music so much as people.

Against curfews and demolitions, the three women's paths cross over a hand-cranked duplicator that smells of methylated spirit and ink. Leela wants to find Sushila; Asha wants the evicted to be named before they disappear into the general word poor; Paro wants a job that is more than mopping up after men who point lathis and call it duty. They begin to gather testimonies in sari hems and tiffin carriers, in the margins of a ledger and on onion-skin paper nicked from a news office on Bahadur Shah Zafar Marg. They map broken homes in Daryaganj on the back of bus tickets and record voices in Lorna's cool room where the fan clinks like a coin in a glass. A sub-inspector with soft shoes and a hard jaw, Naresh Tandon, begins to shadow Leela's family after her fiancé, a solicitor keen on competence and compromise, quietly offers to help with a redevelopment tender that would tidy people out of sight. When Asha's nephew does not return from a queue for kerosene and Paro uncovers the name her employer has ringed twice in the ledger—Lorna's son, foreman of a bulldozer crew—their secret catalogue shifts from keeping memory to confronting power.

The pamphlets they cyclostyle under a single dangling bulb—Dark Shadow, a register of the removed—slip into the morning rounds of tea stalls and the folded guts of broadsheets. Neighbors read and pass them on with the guilty grace of a shared sweet. The city, knit by rumor and rickshaw bells, learns to say names out loud. Some doors close; others open that none of the women expected. By the time monsoon loosens the dust and the loudspeakers move on to new slogans, Leela, Asha, and Paro have risked families, work, and the thin safety of silence to stitch a new commons of witness across lanes that once kept them apart. In steady, intimate scenes crowded with bookstalls, blue police jeeps, brass lotas, and the sour tang of duplicator ink, Dark Shadow invites readers into a Delhi that hides and reveals in the same breath—a story of women who learn that a line, once set in type, can still be moved by hand.