- Pensive west of Ireland mood

- Archive tape conceit adds texture

- Meandering middle stretches

- Security speak sections feel padded

Readers who favor procedural atmosphere over chase scenes might manage, but anyone seeking sharp escalation will drift.

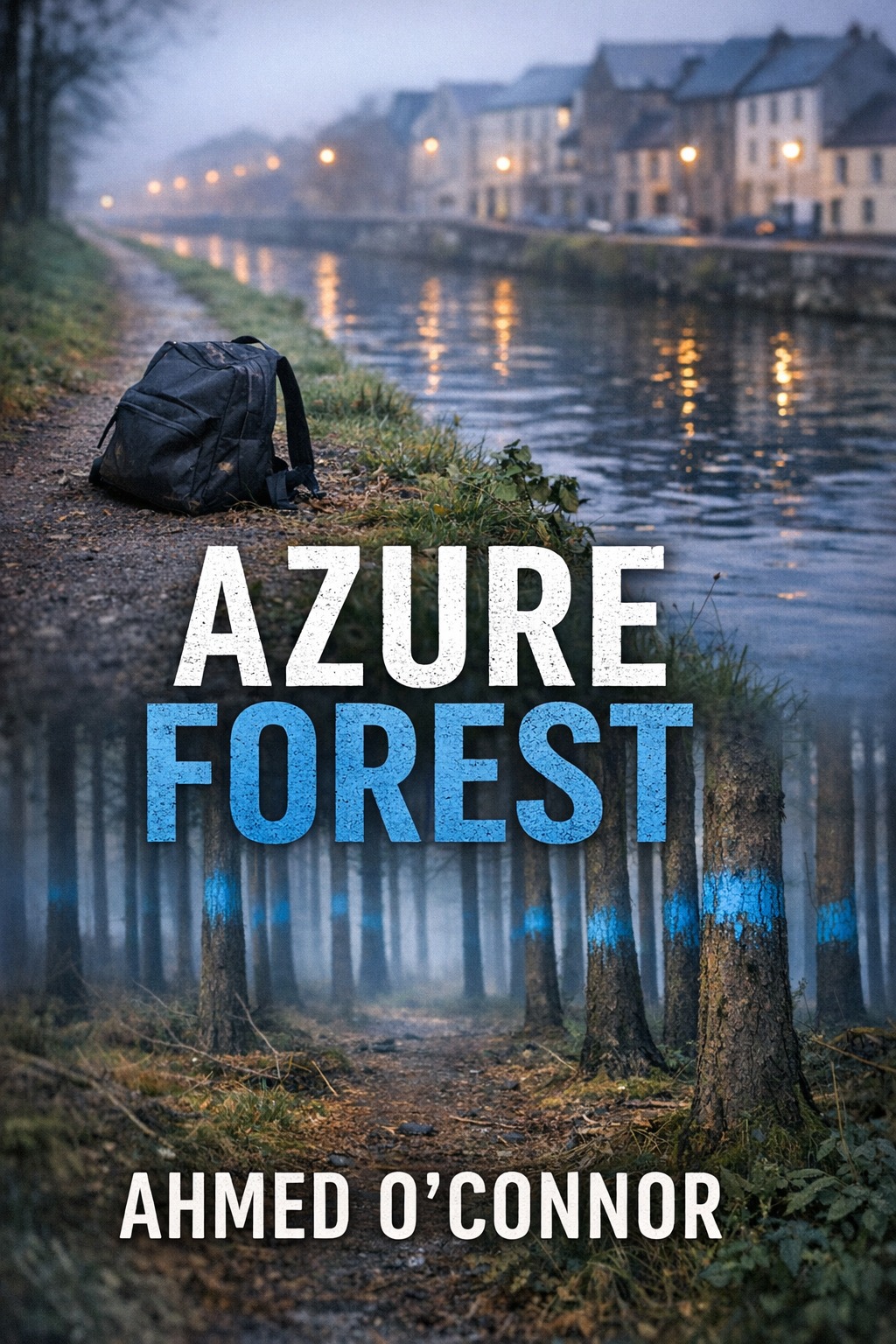

An empty backpack on the canal towpath in Galway, blue spray on the trunks of a plantation outside Gort, and a name that sounds like a promise: Azure Forest. Keelin O'Dea, a community archivist who has spent years coaxing stories from damp cassette tapes and reluctant elders, is ordered to take leave after a public row with a wealthy donor who wanted a testimony excised. Bruised by the reprimand and the quiet politics of memory, she hears a frantic voice note just after midnight from Blessing Okoye, a former participant in her oral‑history workshops, now working as a junior surveyor for a carbon-offset forestry firm. Blessing says she has a little boy, that a white pickup has followed her for days, that the blue marks on the trees are not random.

When Blessing vanishes, Keelin finds only a battered survey stake wrapped with blue tape, a laminated grid listing Compartment 17B, and a microSD card stuffed into a matchbox: digitised reels labelled Coill Gorm, 1982. The recordings speak of a sawmill accident, a missing ledger, and timber lorries that drove at night along the back roads above Lough Derg. They name names—O'Malley Timber, a councillor called Fiach O'Malley, a security contractor set up by veterans fresh home from UN tours.

Following OS maps and the voices of the dead, Keelin drives the forestry roads of the Slieve Aughty, past shuttered hardware stores in Scarriff and a filling station in Portumna where the diesel pumps are chained at dusk. Azure Forest, a glossy rewilding partnership with ÉireCarbon plc, has fenced the old commonage and posted wardens with radios. The Gardaí prefer not to get drawn in. Locals close their doors. In the gaps, people get lost.

A war is brewing between a loose Freeholders Association who insist on ancient grazing rights and a ruthless security outfit led by Niall Broderick, a former sergeant who teaches night classes in perimeter control and calls it community safety. Checkpoints flower at gates. Wind turbines are sabotaged. Rock salt goes into diesel tanks. In the middle are migrant workers without papers—Filip Stancu among them—and Blessing's toddler, left with a neighbour who will not answer the bell.

Keelin risks everything she thinks she knows about keeping records and staying neutral. She uses her archive pass to pull a bound volume of minutes from a company basement in Ennis, takes a secretive meeting in a boarded-up parish hall, and follows the tapes to a decommissioned Bord na Móna yard near Whitegate, where pallets are stacked to hide a container with a false wall. The blue-marked trees form a perimeter. There is a shotgun in the back of a gator, a box of children's shoes, a carbon-credit ledger with two sets of names. An old sawyer's story about an arms cache sunk in a bog turns, abruptly, into a map.

The west keeps its own archives—in peat, in water, in people. As fog lifts off Lough Graney and the radios crackle in the undergrowth, Keelin must decide what kind of witness she is, and how far she will go for Blessing and the boy. Azure Forest promised restoration; what it shelters is older and more ruthless than any planting plan.

Readers who favor procedural atmosphere over chase scenes might manage, but anyone seeking sharp escalation will drift.

Across its fog and forestry lines, the novel keeps returning to testimony, to who controls the archive, and to how land gets rebranded as a marketable virtue. The tapes from 1982 echo the present without neat answers, and Keelin wrestles with being both collector and participant. I liked the recurring idea that "the west keeps its own archives", even when the plot knots up, and the book is most persuasive when it asks what restoration means for people who were never invited to the ledger.

I am furious at how this story hides behind procedure while women and children vanish into the trees.

We get blue tape wrapped on trunks, radios barking in the undergrowth, men with checkpoint lanyards, and yet the pace dithers when it should strike. No, I am not buying it.

Keelin raids a basement, follows tapes, reaches a container with a false wall, and the book stares at its own paperwork. Where is the pulse.

The security talk feels like a brochure, the Gardaí shrug feels like a shrug from the author, and the bad actors grin through gaps that never close. I felt strung along by forms and ledgers while danger pretended to simmer.

This could have been a howl about land, money, and who gets to speak. Instead it is a file with feet. Enough.

Keelin is sharp and principled, but her shift from neutral recorder to solo operator feels sketched more than earned.

Blessing flickers in and out, mostly through messages and reports, which keeps her vital but distant, and Filip is a caution sign rather than a person. The conversations around commonage and security sound like position papers, not people under pressure.

Keelin's archivist eye guides a structure built on interleaved tapes, minutes, and field notes; the atmosphere thickens, but scenes sometimes read like prepped exhibits rather than living story. Chapters close on hints and return to different threads a beat too late, so tension leaks away even when the terrain is charged. The prose is clean and local detail is careful, yet dialogue often lands as testimony instead of talk.

The blue spray and the empty backpack promise a taut chase but the drive through forestry roads stalls often and the resolution limps.