Curator's note: An alternate jacket design is known to circulate.

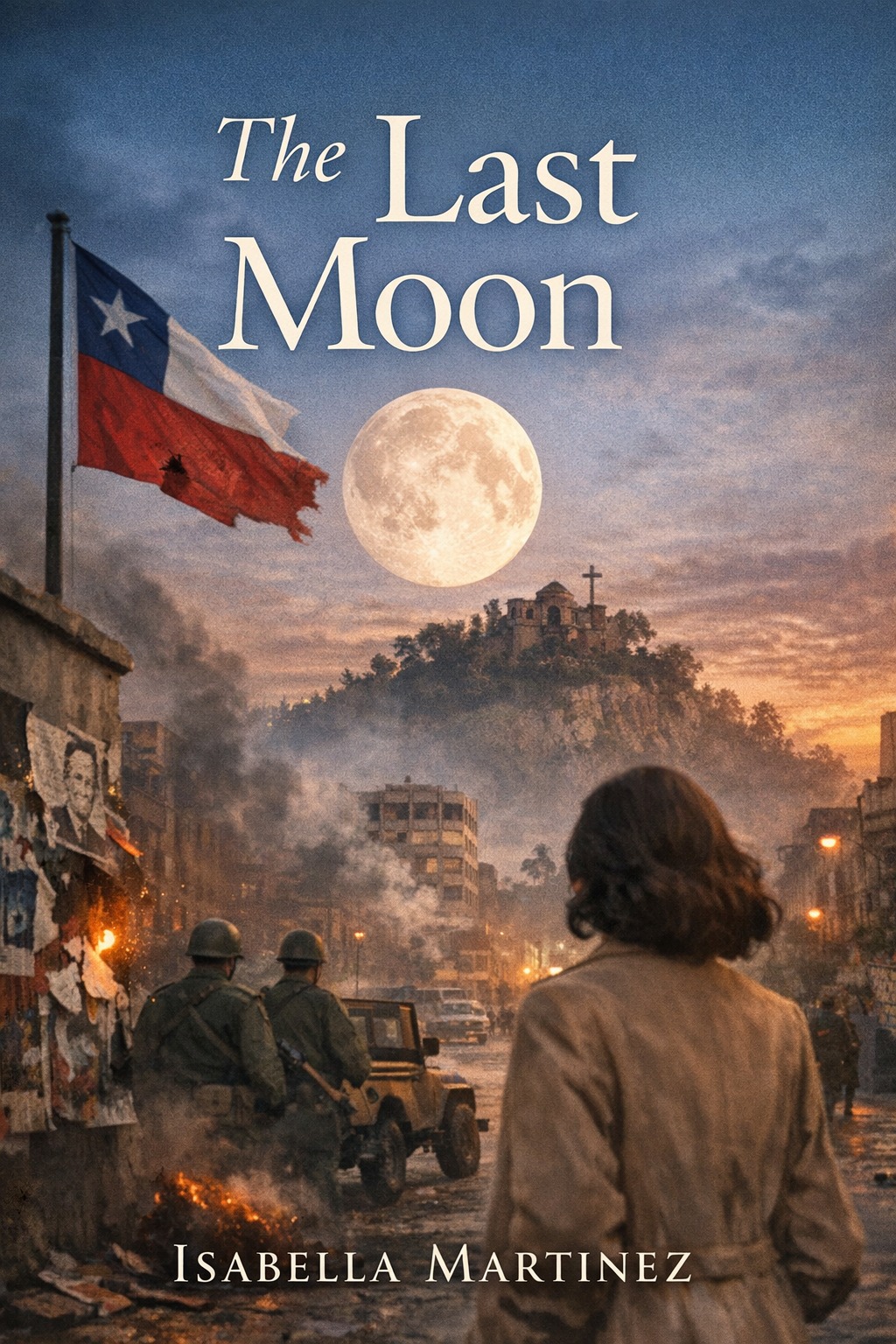

It is September 1973. Santiago, Chile. The streets hold their breath. Sirens splice the morning; posters curl and blacken; radios fall to static. Over Cerro Santa Lucía, the last clear moon hangs like a witness no one invited.

At a vigil in a candlelit apartment on Calle Agustinas, fifteen-year-old Paloma Ibarra slips her hand into her father's wool coat and feels a hard edge sewn into the lining: a cassette tape, unmarked, its reels gleaming like two pale eyes. On it is the banned voice of the vanished poet Álvaro Salcedo, reading verses never printed. What begins as a rescue becomes a devotion. With the guidance of Don Abel, a night-shift janitor who coaxes songs from a battered bandoneón and keeps a dusty Remington upright in his closet, Paloma learns to thread words through machines.

By dusk she pedals a footpress in a hidden back room off the Mercado Central, striking broadsides on onion-skin paper; by dawn she tucks slivers of poems into loaves from Panadería Sol, hides spools in hollowed-out soap. She scavenges melodies from scorched sheet music at the Conservatorio, maps silence along the Mapocho, and memorizes which windows stay dark when trucks prowl.

Then the knock that redefines a life: her mother shelters Tomás Quiroga, a longshoreman with names in a notebook and a bullet graze under gauze, beneath their loose kitchen tiles. Paloma's city unfurls and shutters at once. Under curfew, under whispers, under that unblinking moon, she must decide what a voice is worth, and how far a handful of paper can travel against a night that will not end.