The NHK special hook feels engineered and the folklorist's cool voice flattens the family drama, leaving a graceful concept without enough heat to carry it.

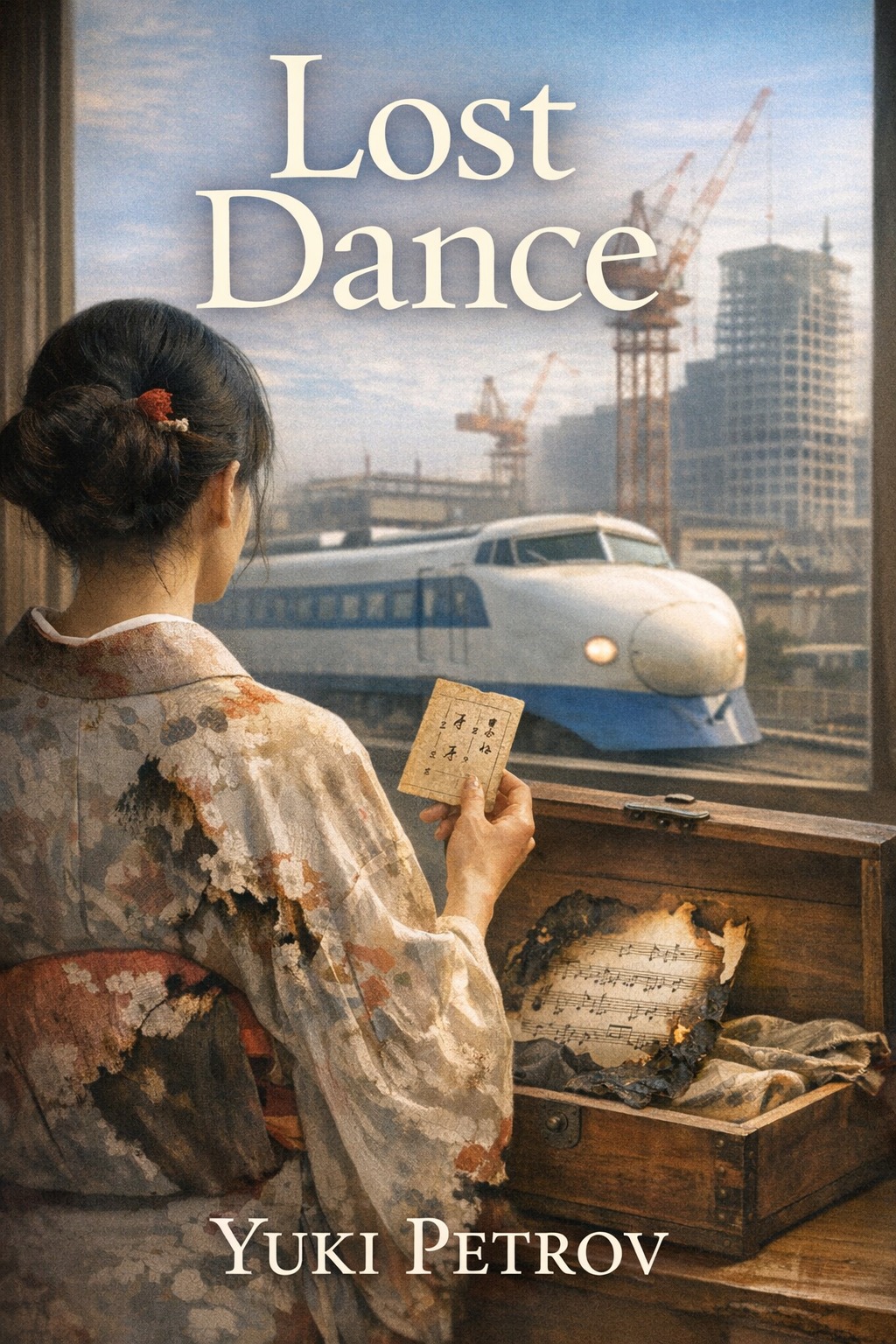

In the summer of 1964, as the Shinkansen's first bullet-blue cars are polished for their maiden run and cranes gnash at Tokyo's skyline, the Morioka family unlocks a cedar chest in their Asakusa dance studio and finds a charred score, a moth-eaten kimono, and a single notation card for a choreography everyone calls the Lost Dance. Before the war, Ayame and Haruto Morioka led Aoi-ryu, a celebrated school of classical dance whose students floated like paper lanterns along the Sumida River festivals and headlined revues at the Kabuki-za. Firebombing, hunger, and the dizzy new steps of occupation-era jitterbug swept their world away. Now NHK wants a live special on vanishing arts, and the producers promise the Moriokas a stage—if they can restore a masterpiece no one has performed since 1939.

Ayame, her toes gone cold inside white silk tabi, insists the steps live in her bones; Haruto keeps a locked drawer of folded letters that could unravel who first devised the dance; their steady son Keiji hides the truth of his after-hours life with a Ginza jazz pianist; and Sayo, who once charmed movie cameras at the Nikkatsu lot, limps after a rehearsal accident the doctors say was nothing. When Haruto is injured during a scaffolding collapse in a Shinjuku rehearsal hall, Ayame defies the elders of Aoi-ryu and hires Naho Ishii, a young folklorist from Waseda with a tape recorder, an opinion on everything, and a stubborn question: who gets to decide what tradition remembers?

From incense-thick backstage rooms to smoky coffeehouses along Kappabashi, Lost Dance traces a family stitching the past to the present, step by step. Funny, tender, and quietly defiant, it asks whether a choreography can hold a country's memory—and whether the Moriokas can shape a future before the cameras roll and the music starts again.