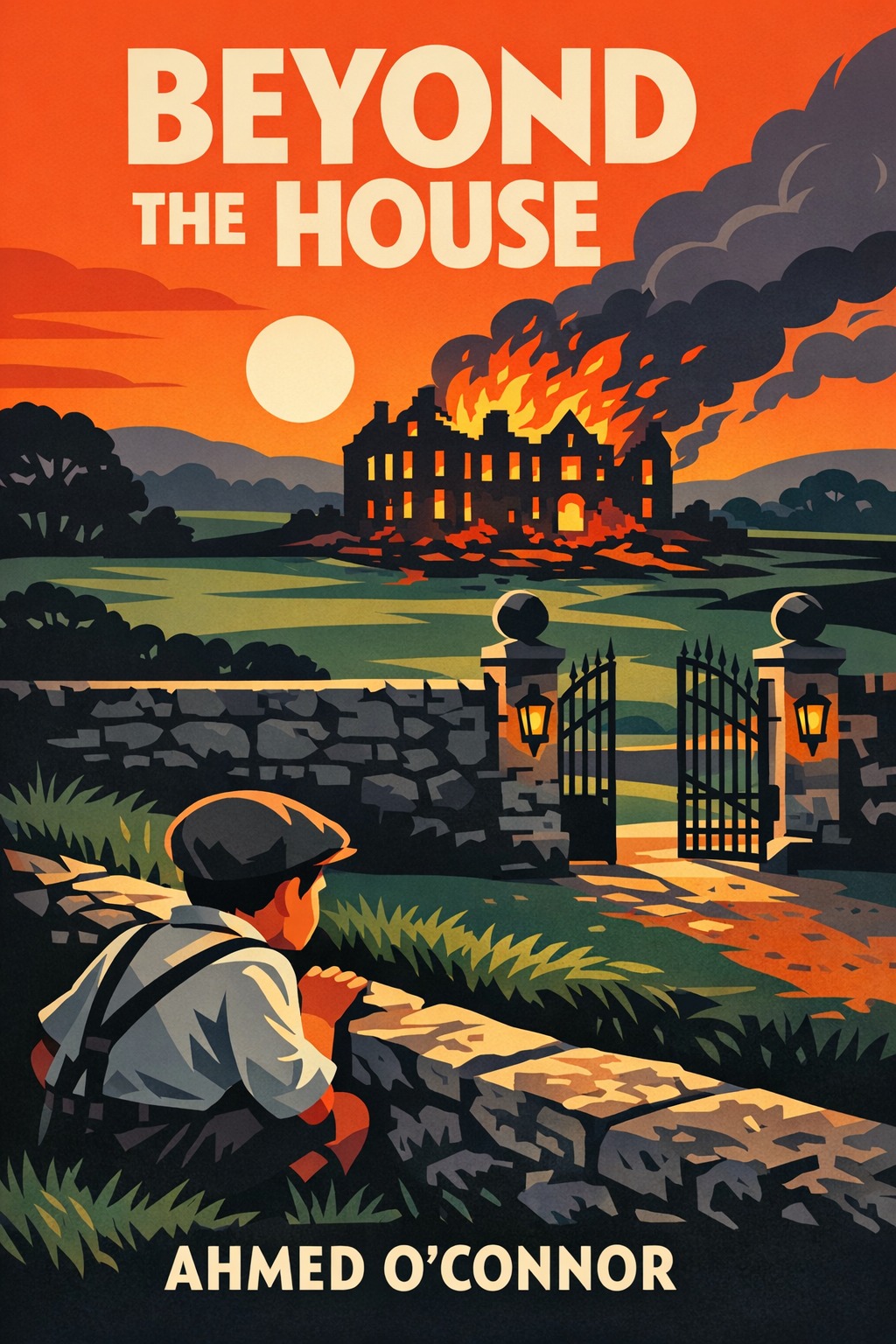

A ruin smolders in memory. A wall keeps a vow. Who are we when the gate finally swings open? On a windless July night in 1922, eleven-year-old Finn Mullan crouches beside the ha-ha at Carrowmore House, outside Gort, County Galway, while his mother scrubs the scullery floors inside. Lanterns bob like fireflies along the avenue; men with muffled mouths pass a tin of petrol hand to hand. By dawn, the great rooms are an orange throat. In the smoke and racket, Finn snatches a dented biscuit tin from the library, a thing he does not understand—a silver locket, brittle letters, a hand-drawn plan of the walled orchard beyond the house, and a small ledger of rents and names. He thinks he sees a figure crossing the lawn, hears a key fall against stone, and watches the glasshouse burst. Long after the ash cools, he cannot forgive what he failed to say, or to save.

In a brick semi in 1975 Hounslow, Noura Kennelly is the only child of a Cork mother and a Moroccan father whose marriage has thinned to courtesies. She is quick and restless, an archivist-in-training who hoards questions she is not allowed to ask—why her mother, Eileen, keeps a Foxford blanket wrapped around a cedar box; why there is no wedding photograph; why Noura's recurring dreams taste of quince and peat smoke, why the name Carrowmore is written on a torn tram ticket hidden in a tea caddy. When a letter arrives from Galway, folded around a pressed sprig of rosemary and signed by P. J. Mullan, stonemason, Noura follows a thread across the sea. In pubs thick with turf, in parish ledgers and the chill of a mossed well, she finds the orchard gate and the map to what the village never put in writing: a gardener scapegoated in a season of reprisals, a seamstress who fled, a silence kept for fifty years. Beyond the house, under a length of rusted chain, lies a tin and a name. What Noura chooses to set down—and what Finn finally admits—will test the stubborn loves of a place and stitch new cloth out of old griefs.