Una novela de voces clandestinas y ciudad fantasma, donde Yue, Nora y Rosa convierten pronósticos del tiempo en memoria colectiva con una ternura y valentía que persisten.

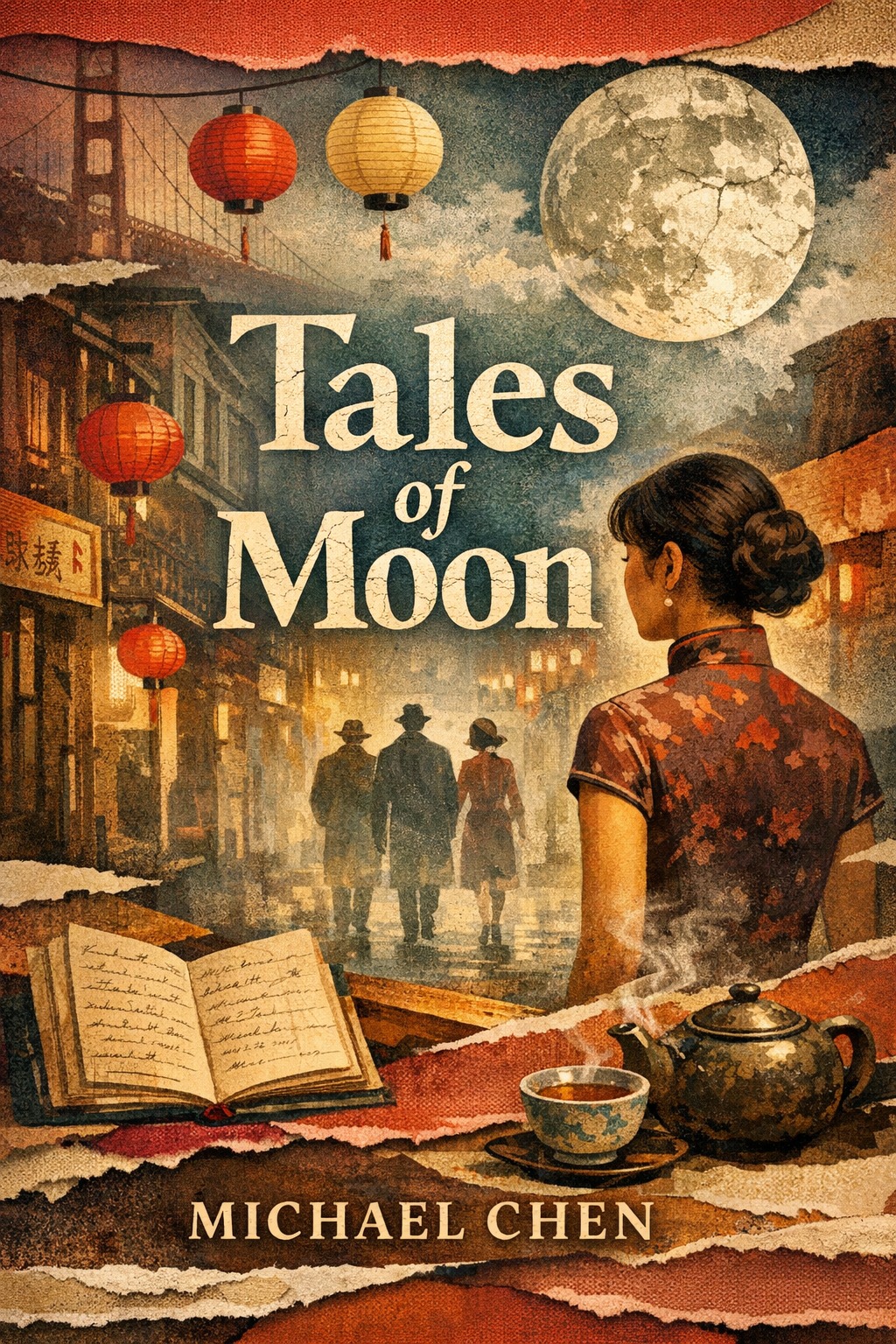

On fog-salted nights in 1930 San Francisco, three strangers lean toward the same thin bright thread: a story someone is trying to smother. Lin Yue, twenty-four, keeps the ledger at her aunt's teahouse on Waverly Place, a narrow room strung with paper lanterns and a cracked mirror shaped like a moon. She can balance accounts faster than she can stitch hems, and she hides copied poems from the Angel Island barrack walls between the receipts. Yue's fiancé waits with a ring and a sturdy grocery in Oakland, but her father has vanished after a "paper son" interrogation on the island, and every official she asks smiles and says there is no record. Yue is certain records are only as real as the hands that write them.

Across town, Nora Keegan, an Irish American typesetter at Whitcomb & Sons on Market Street, feeds an Underwood with headlines and ad copy, careful not to smudge the ink she isn't allowed to sign. She wants a byline that doesn't vanish with the morning trash. After her younger brother fell off a pier while the foreman looked away, Nora started taking notes—names, dates, the color of a longshoreman's coat, the way a policeman taps his baton against a wooden crate when he wants someone to move. Nights, she slips into the KPO radio studio to read weather and lighthouse reports. Between the shipping forecasts, she hears rumors in the switchboard chatter: coded lines, midnight calls from the barracks, stories that will never be printed.

Rosa Delgado, small and sharp-tongued, left Ilocos to gut salmon in a cannery and then to scrub pans in North Beach. She is a comet in a city that keeps trying to put out its own light. Rosa has a knack for making trouble sound like a song. She passed out union cards until she lost her job; she called a foreman a thief and found her cot gone. The only work left is at the Moon Gate Hotel, a place too new to know her reputation. The owner, Mrs. Lillian Vaughn—widowed, wealthy, and wearing grief like a silk shawl—seems almost eager to hire Rosa. But there are locked doors upstairs, and more than one name carved into the underside of a dresser drawer.

They should have stayed in their lanes: daughter, typesetter, dishwasher. Instead they invent something that can slip through the lattice. They call it Tales of Moon, a midnight radio drama smuggled between weather reports and sponsorship jingles, a chorus of folktales and ghost stories that are also maps—names of ships disguised as river gods, badge numbers tucked into proverbs, interrogation questions braided into a legend about a girl who can read the tides. Scripts are hidden in mooncake tins and laundered through the teahouse till, then carried under coats past Portsmouth Square to a studio where Nora keeps the door propped with a stack of misprinted calendars. Yue, Rosa, Nora—women from streets that rarely cross—begin to stitch a record big enough to hold the people everyone insists are only shadows.

The risk is not theoretical. Men from City Hall hear the radio in their clubs and understand that folklore can speak plainly. Consular officials frown over missing files. A patrol officer recognizes Rosa's laugh. In alleys that smell of star anise and machine oil, in the ferry line beneath the Ferry Building clock, in the chalky echo of the Angel Island barracks, the city tightens its belt. But once a story learns how to walk out of a locked room, it does not forget the way. With wit, ache, and the stubborn grace of people who have more to lose than their names, Tales of Moon traces the unquiet making of an archive—a record born out of kitchens, print shops, and night air—about the lines that hold a city together and the ones that have to be crossed to make it worth living in at all.